I was playing at an online ACBL game last Thursday and two consecutive hands presented an interesting theme — whether one should open with 12 hcp in a balanced hand.

Before looking at the hands, if you asked me about this, I would estimate that I open more than 50% of those hands, but not all of them. Important criteria are spot cards, which suits I actually hold, position, and vulnerability.

The first one was

♠️ 1093 / ♥️ Q97 / ♦️ A87 / ♣️ AQ42

With no one vulnerable, dealer passed and it was my turn.

Let’s look at each of those criteria listed before.

Spot cards — under average. The ♠️109 are nice, and the ♥️9 may combine with something over there, but this is only a “maybe” at this point. There are no spot cards combining with the honors in my hand, which would be a certainty rather than a possibility. This hand would be much improved if I had ♠️543 and ♣️AQ109 instead.

Shape and suits — 4333 is horrible as we all know. Having clubs as my 4-card suit does not help. The chances that we will declare this hand if partner is weak are quite slim. And if we will not declare, the less we bid, the better for us. Declarer will play more accurately in whatever contract they reach if I open the bidding.

Position — The 2nd seat is the “adult’s seat”. It does not pay to push too much here, since one of our opponents has already limited his hand. Partner will (should!) open in 4th position with any balanced 13 (even if weak in spades, by the way), and with any unbalanced 12, which means that our pass here will never, almost never, hardly ever cost us a game. Of course, we may lose a partscore if the hand is passed out and partner had 10-11, since we will have the balance of strength, but this possibility is lessened by the fact that our best suit is clubs (i.e. if there is bidding, we might be outbid). The evaluation would be different if we switched our clubs and our spades.

Vulnerability — No one vulnerable is very conducive to a contested auction, and participating in a contested auction with a balanced hand is no fun. If we were not vulnerable and the opponents were vulnerable, again the evaluation would change. The opponents might leave us alone in 1NT or 2 of our best suit if we open. But with no one vul it is quite likely that they will be in the bidding and we don’t want to play at the 3-level opposite a weak hand.

Note that all of this discussion is predicated on partner having a weak (5-10) balanced hand, because that is the most problematic scenario. If partner is weaker than that, they have a shot at game (and we do not want to bid); if partner is stronger than that, he will probably be bidding on his own; if partner is unbalanced and has a nice suit of his own, he will probably be bidding on his own, again.

Anyway, I passed and the bidding continued with 1♦️ on my left, followed by two passes.

Now we are at a typical balancing position. The opponents have limited their strength, so partner should have something, and my reopening 1NT shows 10-12 hcp with a balanced hand, which is what I have. That ends the bidding:

The lead is the ♦️K:

Look at the effect of your choice in the first round of the bidding. You are already in possession of an important piece of information that you would not have had if the bidding had been, say, 1♣️-1♠️-1NT, which is that the 21 missing high-card points are concentrated in West, to the tune of 16-5, 17-4, or similar.

Of course, the fact that West has so much means that he would probably not have passed 1♣️. But since he does not have a club stopper, his choice would have been 1♦️ or double. We don’t know yet how many diamonds he has, but we know that if he had started with a double, it would have been much easier for the opponents to find their heart fit.

Anyway, you duck the first diamond, and win the second, as East follows suit with the ♦️3 and the ♦️4. When you cash the ♣️A, West plays the ♣️J. Now it looks like his hand is 4441, but it might still be a 5431 with five diamonds, since East’s cards should not show count, but rather attitude for the ♦️J.

You run your clubs ending in dummy, and West discards the ♥️5, then the ♥️2, then the ♥️J. You know now that he is stuck with a singleton heart honor, so you play a heart, duck in your hand, and see him winning the ♥️A.

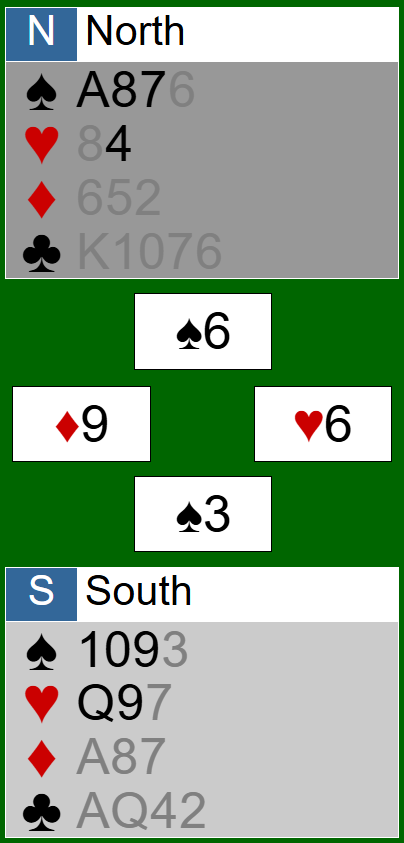

He cashes the ♦️J, as East follows with the ♦️10 (so, 4441 in West). When he cashes the last diamond, you discard a spade from dummy, East discards a heart, and you discard a spade from your hand. This is your ending at this point:

You expect West’s last four cards to be spades, as East holds two spades and the ♥️K10 in hearts.

West plays the ♠️Q. That is a nice card to see, since East would not have passed in 1♦️ with the ♠️K (in addition to his known ♥️K), and the only maneuver that the defense could to to prevent us from winning the ♥️Q in this ending would be to win the first spade in East, enabling him to cash the ♥️K and exit with a spade. The ♠️Q prevents that. So we duck this trick, win the next spade, and play a heart from dummy. We score the ♥️Q in the last trick to make the contract.

The full hand:

The defense slipped, of course, most notably by discarding the 3rd heart from West, but also by not switching to a low spade at the 4-card ending. I think the most interesting aspect of the deal, though, is the impact of the bidding on the play.

Passing 12 hcp balanced hands should not become a habit. But curiously enough, I had the opportunity for another such pass in the very next board! But that is for the next article.